In JRB's excellent video on his drafts of opening numbers for The Connector, he describes three functions of an opening number in setting up the world of a show:

- The number needs to establish the setting of the story and evoke the community it concerns.

- The number needs to establish the rules of the show. How is music being used to tell the story? What's the tone of the piece- what will and won't be on the table, in terms of storytelling technique?

- The number needs to establish a thematic hook for the audience to follow through the show. Why this story- why is it worth telling, and what's it all really about?

In Working On A Song, Anais Mitchell talks about the demands of dramatic songwriting:

"[When I get my hands on another copy of the book, I'll find the quote, but it's about how rendering a situation poetically isn't enough for music drama- there's got to be a Situation unfolding]"

Put these two critera together, and it's clear why an opening number is such a tall task. Not only do you have a lot of musical exposition on your hands, you have to frame it as action, as characters in a place doing things with forward momentum. I struggle a lot with putting these together, and often times, my first draft of an opening number will be word vomit into the vessel of song structure, a mere receptacle of the necessary information, exposited unadorned. Only later, with a better grasp of where the show needs to go and where I need to direct the number's momentum, will I squeeze that information into the corset of dramatic action.

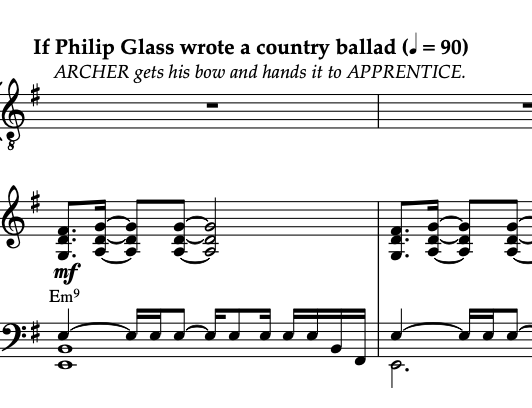

For example, the first draft of "Ten Suns" started like this (parentheticals sung by the Emperor):

WHEN THE EARTH WAS WILD AND YOUNG,

TEN SUNS WERE HUNG

UP IN THE SKY

AT THE EMPEROR'S COMMAND, (TEN SONS OF MINE,)

THEY SCORCHED THE LAND (THEIR WILL DIVINE)

PEOPLE WOULD DIE

(AND ALL LOOKS RIGHT FROM HEAVEN,

ALL IS RIGHT IN PARADISE,

ALL IS PERFECT FOR MY SONS)

SUNS DON'T CARE IF PEOPLE BURN,

THEY CANNOT LEARN,

THEY CAN'T BE KIND

SUNS BRING HUNGER, SUNS BRING DROUGHT,

THEY KEEP US OUT,

THEY MAKE US BLIND,

SO WE REMAIN YET BLIND...

...and the Archer went on to sing.

In theory, this lyric contained all the information necessary for the audience to understand the story to come. In practice, its unstructured unpacking led to confusion in test audiences. Who are these characters? Where are these characters? Why should we care that these suns/sons are giving them a hard time?

While I was trying to find a backbone for the song, another issue presented itself. The song was a lot of naked complaining. It set an unpalatably heavy, dour tone, and it wasn't emotionally genuine; I feel like the harder times get, the more necessary humor, levity, and flippancy become in confronting and enduring them. The song, in dealing with mass suffering so bluntly, robbed the situation of its human edge, and as such its human stakes.

The eventual final draft of the song has the laborers playing a game of "I have it worse" one-upsmanship with each other. Like magic, that well-defined form of that dramatic framework solved all my problems. By having characters, instead of the omniscient Ensemble, parcel out the information, the audience could digest it more easily, both intellectually and emotionally.

|

| I looked up "suffering olympics" and got this. -Z |

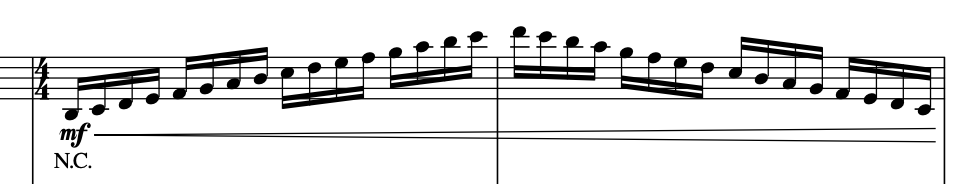

"Those unlucky ones/had to brave ten suns..."