You don't want to hear a composer sweat, you want to hear a character breathe.

Woah. That's a beast of a time signature. How did we end up here?

AGAINST SYMMETRY.

I have some history as a singer, and one of the things I find most uncomfortable to defend with my voice are pauses where the character needs to wait to catch up to the music. I simply don't know how to hold the stage during silences, or broken-up words or phrases, written in to accommodate the needs of a symmetrical and regular musical structure. It feels, to me, like an inversion of my priorities as a singer; in that moment, instead of me using the music as a tool to illuminate the character, I have to use the character as a tool to illuminate the music.

As masterful songs like Ring of Keys show, it's quite possible to load musical symmetry with dramatic meaning, and give breaks in the vocal flow a forward-pushing dramatic purpose. But when I write, I'm much quicker to consciously upset these symmetrical structures when they impede the flow of the drama. (I'm talking about structures like 4-bar phrases, songs that stay in 4/4 or 3/4 throughout, that sort of thing.) I find this makes for more convincing singing characters, and music that's harder to get ahead of as a listener.

THE VERSE.

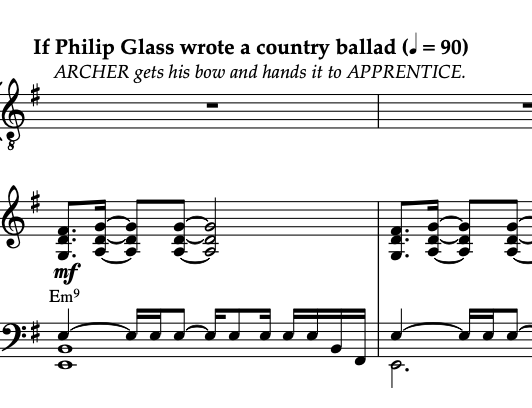

Here's an excerpt from Wife's verse:

You'll notice that there's no full beat of rests between phrases. A very early... not even draft, but working-through of the verse... had that same melody, with that full beat of rest, in 4/4. When I listened to myself sing it, I always found that hiccup of silence arrested the flowing momentum of the vocal line. By taking out that last beat of silence, the song took on a lived-in lopsidedness and warmth; it, metrically, spoke to an old love weathering its being knocked off-kilter. To better communicate the regularity of this phrasing, I used the compound meter 4+3/4 instead of alternating 4/4 and 3/4 measures.

THE FORM.

"You Go" has an ABABC form. The verses are expository, in the third person. The choruses are aspirational, in the second person. The bridge is a moment of stability and unity in the imagined space the characters spend the song carving out for each other. The stability of the stability of the bridge suggested the familiar, comfortable clockwork of 4/4.

The musical story I needed to tell in the choruses, then, was a pull away from the oppressive humdrum of the verse, but not to a place of metrical stability, as to make the bridge maximally satisfying when it finally resolves the rhythmic tension. This suggested to me a double-time groove: a burst of energy that only heightens the pulse's sense of unevenness.

In none of these cases was I consciously imposing musical complexity onto the song for its own sake. The point of every musical decision was to shorten the distance between the musical tapestry and the psychological situation of the moment. The songwriting, however intricate (or pared-down), always serves to give the characters the best avenues by which they can express what's happening to them. If the audience ever becomes aware of the musical artifice, the illusion of musico-dramatic seamlessness falls, and the spell the piece is casting is broken.

Or, in short: you don't want to hear a composer sweat, you want to hear a character breathe.

"But time keeps pushing me/and if I lose my grip, then I leave for good..."

No comments:

Post a Comment